There have been a lot of books published recently on leadership in modern history, whether it is due to the unsettling times we are in, the gloomy character of our political leaders, or the growth of right-wing populism.

The format appears to be to link together chapters on many great leaders who altered history, for better or worse, and consider the patterns between them, from Frank Dikötter’s How to Be a Dictator to Henry Kissinger’s Leadership.

The most recent book is Personality and Power by Ian Kershaw, a famous historian of Adolf Hitler and his movement. In this book, he paints 12 clear images of the leaders who molded the 20th century in Europe, half of whom were dictators and the others, to varying degrees, were democratic.

The quote from Karl Marx from 1852 that serves as his starting point is, “Men produce their own history, but not as they wish, in conditions of their own choice, but rather under those immediately faced, given, and inherited.”

Kershaw questions how much the circumstances and how much the leader’s personality influence the leader’s strength. The subordinate problems in each chapter are presented in the same order, starting with the conditions that led to the leader’s ascent and ending with a brief examination of his legacy.

The charisma of the leader is either produced for him by his movement or the state through a personality cult, according to Max Weber’s theory of “charismatic” leadership, or it is made for him by his followers of believers, whose ideas are invested in the “chosen one,” in Kershaw’s work. The inventor of this strategy was Kershaw. The Hitler Myth (1987), one of his best early works, demonstrated how Hitler’s political influence depended on the public’s perception of his promotional image.

He makes a point of highlighting how crises produce outstanding leaders. This holds true for leaders in democracies whose greatness came as saviors of their country in a time of war (Churchill and De Gaulle) or for those who guided their country to democracy after ruinous dictatorships (Lenin, Mussolini, and Hitler), as well as dictators who came to power through social revolution, parliamentary politics collapsing, or economic depression (Adenauer, Gorbachev).

Kershaw may have emphasized this point more: crises can also be manufactured. Stalin was able to defeat his rivals for the presidency and push through his version of the five-year plan thanks to the “war scare” of 1927 (when Pravda published false information about a British invasion of the USSR), and Mussolini and Franco were able to rally terrified Catholics to their cause by stirring up anti-Bolshevist fears.

In his engaging portraits, Kershaw includes important insights into the personalities of the leaders, their methods of operation, and their interactions with the institutions of power that gave them support.

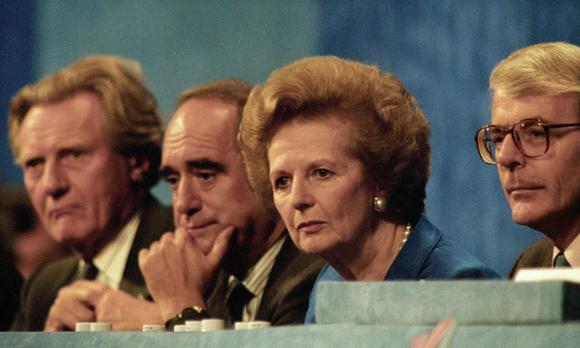

In order to “carry her case against cabinet colleagues who were less well prepared or more docile in their character,” Margaret Thatcher “thrived on caustic argument and confrontational dispute,” depending on her “workaholic habits” and “forensic interrogative powers” as a professional lawyer.

By forbidding bathroom breaks during sessions that may continue all day and all night, Franco broke down the resistance of his ministers. He had “amazing” bladder control, says Kershaw.

He analyses how far these errors can be attributed to leaders’ own stubborn personalities, ideological blinders, or the hubris that so many leaders, especially dictators, experience when they have been in power for an excessive amount of time. He also highlights the errors that led to leaders’ downfalls.

Only in retrospect do such errors become clear. If Putin’s invasion of Ukraine fails, it will be seen in Russia’s history as a mistake; but, a “win” will obscure the nation’s recollection of the massacres and military gaffes. Power makes all decisions.

As one might anticipate, Kershaw’s sketches of the three German commanders in this book display his mastery to the fullest. In addition, he is an expert on Mussolini and De Gaulle. His use of secondary sources results in a flat and conventional description of Lenin and Stalin, which makes him less persuasive.

He lacks a thorough understanding of the Byzantine tradition of saintly tsars and princes, which evolved into the cults of Lenin and Stalin, nor of the patrimonial nature of autocracy in Russia, where the leader is the master of the land and its people, a form of despotism and enslavement of society that dates back to the Mongols and continues through Stalin (“Genghis Khan with a telephone,” as the Bolshevik Buk Russian’s word for power, vlast, derives not from an activity like it does in western languages like puissance, Potenza, Macht, etc., but rather from the word for a fiefdom, a region that belongs to its monarch.

In the last chapter, Kershaw summarises the elements that each of the 12 leaders in the book used to define how they used their authority. His goal is to evaluate seven claims regarding personal leadership, as he states at the outset. Each one is quite evident.

To learn, for instance, that “a singular individual can stand out and attract a following” through “single-minded pursuit of plainly stated goals and ideological inflexibility paired with tactical competence,” did we really need to read this book? is the idea that “concentration of power boosts the potential impact of the individual – typically with negative, perhaps catastrophic consequences”?

Perhaps, in the end, the cultural distinctiveness of the seven nations this book examines, and their various histories of conceptualizing power and authority, do not lend themselves to generalizations as readily.

Is it even useful to contrast the styles of rule under regimes as dissimilar as the Third Reich, Tito’s Yugoslavia, or the United Kingdom under Churchill and Thatcher? I’m not sure if there are any overarching lessons to be learned from Kershaw’s persuasive and perceptive examination of these powerful individuals, but there is much to be admired in it.

The author of The Story of Russia is Orlando Figes (Bloomsbury)

Irving is the Chief Editor at the Landscape Insight. He lives just outside of New York. His writings have also been featured in some very famous magazines. When he isn’t reading the source material for a piece or decompressing with a comfort horror movie, Irving is usually somewhere in his car. You can reach Irving at – [email protected] or on Our website Contact Us Page.